Resilience and the Stockdale Paradox

A Brief Introduction

There has been one overarching macro thesis of venture capital for the last twenty some-odd years: the cost of networks (and network connections) dropping to zero. This has been true, and has made investors billions, even when investors had no idea this was their thesis. Everything has been part of this, with collapsing connection costs driving the cloud, social media, mobile apps, political unrest, and so on. The majority of value that has accrued in this cycle was to centralized platforms. We believe that this long-standing macro cycle is approaching its natural limit, to the point where the collapse in costs isn’t predictably producing valuable companies the way it once did.

So, what happens next? Some are now arguing that “web3” (blockchains and NFTs) is the next macro-wave for venture capital, specifically that we’ll now see a meta-cycle of the collapsing costs of decentralized networks. And, while it may be true that value will accrue to that area as well (and we’re optimistic about some aspects of “web3”), we’re doubtful that the next macro-investment theme for all venture capital will simply be a rehashed and remixed replay of the previous macro theme.

As we pull back in an attempt to think about the future, our first move is to think in longer cycles. Of note is that when we say we’re thinking in longer timeframes, we actually mean we’re thinking in longer timeframes – where ten, twenty, fifty year time frames are where we begin. We operate on the presupposition that by finding a thesis to explain the long data, we can then work our way backwards into more short to near term investable themes.

This approach sometimes makes us prone to things that sound nothing like the usual “hopium” from other investors, which apparently confuses people. But it shouldn’t. Our approach is modeled after the so-called Stockdale Paradox. Admiral James Stockdale was a prisoner of war at the Hanoi Hilton during the Vietnam war. His approach to captivity was to mercilessly confront all of the data of his situation—the full house, as Stephen Gould once wrote—while not wavering in the belief that he would eventually prevail. This is the Stockdale paradox: One survives by engaging unapologetically with all of the data, however good or bad, while still retaining a constructive outlook.

Most venture investors don’t do this. Out of a fear of ever saying anything that doesn’t seem sufficiently optimistic, they don’t engage with or talk through all the data. “What if it works” is a fine ethos, but “what if that thing that used to work out no longer does” leads to important places too.

Again, this confuses people, like when we talk about the pandemic (ugh), climate (double ugh) or how many bears will be killed by humans this year (far too many). We get asked how it is that we can be venture investors when we’re seemingly so negative. The answer, of course, is that we’re not negative at all—we’re just looking at the full house of data. Like Stockdale, we’re facing the facts as they stand on the ground, and then using that real baseline (not a hyper-optimistic imaginary baseline) as the starting point for finding the investing path forward.

With that in mind, we wanted to share our latest thinking about some big themes we do see ahead, in particular to do with resilience, broadly defined. We think that people are tired of feeling whipsawed by all the forces we have described, from politics, to pandemics, to social media, to, increasingly, the environment. People want to feel less blown about, less at the mercy of forces they can’t control.

It’s worth thinking through how this could play out across many aspects of life. Some of this is highly speculative, some of it may seem obvious, and some of it may be maddening. That is the point of such exercises.

The New Tool

A formerly top-ranked venture capitalist—Let’s call him Tim—who made millions in the 90s dropped out a few years ago, arguing to one of us that venture no longer had a new tool. Having made his money in the personal computer, semiconductor, and network gear industries, Tim saw no waves in the future and couldn’t imagine how a future venture industry could produce returns like its past, especially given vastly more capital and companies.

Tim was wrong, of course. As he dropped out, the next wave was coming: mobility and social were just getting going, two mega-trends that made investors billions in the almost two decades since.

Tim’s error, however, was forgivable: he extrapolated from what had been making money—network gear, personal computers, enterprise software, and semis—and didn’t see the same space for startups that had existed in the past. The key to thinking about the future of venture is to think about new tools in which one can invest, tools that have some growing tailwinds, where an injection of capital can create new markets, or overturn existing ones. Tim was right that the future of his favorite areas wouldn’t make money in the future. Those areas largely haven’t. They did, however, help give rise to new areas, which made investors money.

What is the new tool today? What are the trends sitting on top of the last generation of slowing technologies, like mobile, that will open up new markets? The easy approach is to be extrapolative, and imagine more apps running on mobile, like AR/VR and the like. This is an error, however, in the same way that Tim's experience extrapolating into a future of more PCs and more network gear led him to drop out of venture.

Many will point to web3, crypto, and the like. While they have a point, and there are opportunities there, this is still playing an extrapolative game, rather than breaking free of the past.

What might those new tools be? We think it could be vertiginously different.

Reintroducing Friction

Much of modern tech is predicated on the idea that the cost of connectivity, coordination, and computing have all collapsed. We live, we are told, in a friction-free world. And we do, which has helped make billions for investors in companies exploiting those trends, from social media, to mobile, to software-as-service, and so on. No-one has gone wrong extrapolating that trend, and then investing accordingly.

But two things may mark the end of that investable trend. First, the costs of connectivity, coordination, and computing have dropped to zero, for practical terms, so it’s hard to imagine that they go lower. Sure, there are models where companies subsidize such things that they effectively make their costs negative, but that loss-leader model has capital-consuming consequences.

The other thing that may mark a change in this mega-trend is a growing awareness of its unexpected consequences. A profusion of recent studies show the impact on public discourse, as people become increasingly tribal, partisan, and irrational, retreating into echo chambers of the like-minded. Social media companies have only half-heartedly pushed back on this, and it’s unlikely they can do much more without changing the nature of their businesses.

But politics isn’t the only area where reduced friction has consequences. One of the reasons global trade exploded in recent years was that modern communications technology made it feel friction-free, that one could have suppliers all over the world, and then bring all those products together for end-markets elsewhere. Recent supply chain problems have helped remind us that this sort of thing works until it doesn’t, with dire consequences when it stops. It is breeding a counter-movement, with more local inventories, more on-shore production, and a general push-back against “just in time” thinking, which was formerly sacrosanct.

You can even think about collapsed costs playing into the rise of the current pandemic. Global travel networks carried the virus around the world, with data showing it was essentially around the world by the time the first reports came out of Wuhan in early 2020. We see that again with the current Omicron variant, which was already in Europe and North American by the time we got the first reports out of South Africa. Our inability to think coherently about the consequences of collapsed costs has had immense consequences that can be measured not only in monetary terms, but also in human lives lost.

So, if costs can’t collapse further, and we are seeing pockets of retrenchment against some of the ravages of friction-free life, what happens next? We think we will see, slowly at first, some pushback against friction-free life. Frictions—and they will go by many names, like onshoring, inventory, WFH, etc.—will begin to be reintroduced. People will only realize, slowly, and in retrospect, that the collapse of global frictions began reversing 2020, and that it became a mega-trend, with investable consequences.

Without tipping our hand too much, turn your thinking around. Start thinking about “friction as a service.” What will consumers, producers, and governments begin demanding, however disorganized, and how will startups provide that? In the past we have used the example of Abine’s Deleteme service as an example, but you can imagine a panoply of products emerging in response to this mega-trend.

Energy and Power

The next area worth thinking about is energy and power—which is hugely misunderstood. A quick overview follows, and then some details about the immense changes coming to energy.

There is an energy transition underway, as you’ve been beaten about the head to understand. We are moving, however haltingly, from a more carbon-based fuel system for many purposes to a less carbon-based one. We hesitate to use the word “renewable” because it is somewhat of a misnomer. For example, yes, sunlight for solar is renewable and carbon-free, for practical purposes, but the products used to generate power from sunlight are far from it, as will become important in the coming years.

Nevertheless, there is a transition, just not necessarily the one you were given to understand. From our point of view there are actually two big changes going on. The first is from a more carbon-centric substrate to a less carbon-centric one. Electric vehicles require carbon in their production, even if they don’t burn it, so we need to be clear about what we’re calling things so that we don’t declare victory, having lost all relevant wars along the campaign.

This matters because it means the transition will be longer, slower, less effectual, and more politically fraught than many seem willing to consider. After all, we are fighting endlessly about a vaccine without perfect efficacy for Covid. How much are we going to fight about an energy transition that doesn’t actually entirely transition away from carbon-based fuels?

There is a second transition underway, however, and in many ways it is more interesting than the more trumpeted one described above. The second transition is away from a centralized model of energy production, one where utilities deliver energy from nuclear, natural gas, coal, and solar installations, towards one where the edge of the grid increasingly provides and stores energy. We are heading toward a more diffuse, edge-centric, and intelligent energy grid, one that will seem increasingly internet-centric as time goes on.

What might that look like? We are seeing early rumblings now, with rooftop solar driving costs to negative levels mid-day in parts of the country. It is to the point that utilities are balking at prior purchase agreements that had them paying customers for putting power back into the grid, power that they don’t need at the generated scale. California, which leads the U.S. in solar power, is even proposing dramatic cuts in its support for roof-top solar, a superficially shocking move.

But this is likely only a short-term issue. Homes will increasingly generate and store power, whether in whole-house batteries, grid-connected electric vehicles, or other forms of local and regional storage. We are adding buffers to a system previously built around maintaining expensive slack in the form of plants that could be spun up when needs spiked, like on a hot day.

The future will look more internet-like, with many resources, loosely joined. Consumers will look more like Etsy crafters, constructing portfolios of energy that can store and sell back into the grid at opportunity times, providing immensely more resilience and flexibility to an expensively over-provisioned power grid.

This is very interesting to us. It is potentially capital-efficient, flexible, and small amounts of capital can drive rapid growth. Too much of the energy investments getting all the attention—nuclear fusion, direct air carbon capture, etc.—require immense amounts of capital in pursuit of laudable ends, but ends more reflective of the past of energy production than of the future. Don’t misunderstand us, however: we would love to see a cost-effective capture technology that “un-did” a century of carbon de-sequestration. We’re just not very optimistic that it will happen soon, or with the kinds of modest capital injections that produce venture returns.

Health

Health, like productivity, is everywhere except for in the numbers, as they say. Americans embody that contradiction: They are the most ill people in the western world, but also the biggest spenders on healthcare, gyms, and fitness. The recent pandemic has accelerated all of these trends at once, with studies showing increased blood pressure, and increased weight, but also a boom in personal health startups and Peloton subscriptions.

It’s easy to sniff at this, and assume it will all change if/when the pandemic ends, or at least ends more than it has. But we think that’s wrong. There are deeper forces at work, forces that started before the pandemic and that will continue long afterward.

People are uneasy, and they want control. There are only so many things in their lives over which they feel they can have control, especially ones that feel connected to longevity, especially in the face of a never-ending pandemic. Money is one of them, and we discuss it in the next section, but health is another. While this is sometimes seen as middle-class fussbudget-ry, there is more going on than the over-monied overspending on bad coaches and ineffective dietary supplements. This is another example of people trying to control more things in their life—to build resilience—and it’s not going away, even if some manifestations, like Peloton, become less in vogue.

There are demographic trends pushing this too. Western societies are aging ones, with rapidly inverting population pyramids. Most of the assumptions around economies that have developed are slipping away as the mass market trends toward being what older people want, a “gerontoconomy,” as it might be called. And, consistently, a central focus of people as they age is better managing their health, both in the face of environmental volatility, but also in the face of the health pressures of aging. Call it healthspan, call it what you will, but demographic pressure has now been joined by a drive for more health resilience where the merits of better health have been made much more palpable.

We are seeing some of this play out already. We mentioned the rise of Peloton, and of home gyms. But we are also seeing an explosion in meditation apps, as well as in brain games. Apple’s iPhone App of the Year this year was a meditation product, and a runner up was a brain game. This is a remarkable shift from the days of first-person shooters and Farmville. And it’s a shift that we think will persist and grow, especially in a world that we have repeatedly characterized as subcritical.

There are risks, of course. We aren’t interested in most of what other people like, especially in things like digital instrumented health. An increasing number of studies show that consumer-backed monitoring devices mostly lead to over-diagnosis, to the medicalization of people who didn’t previously think of themselves as ill. It can also lead directly to over treatment, with myriad health consequences. We think the forces behind these devices and diagnostics are important—resilience, aging, and adaptation—but the expression in product and services is both wrong and risky.

Finance, Mobility and Fin-tech

Money is the original hardening. It has always been the way that people insulated themselves against the vagaries of life, that they made themselves more resilient. So it should come as no surprise that some of the most interesting changes in a society trying to come to grips with a newfound need for hardening is that money is at the crux.

But as is so often the case with such deep changes, it is largely misunderstood. Too much of the discussion about financial technology is about paving cow paths, about automating what has gone before, or making it less friction-filled. Or, more insidiously, it is novelty tech, new ways of transferring things or attaching value to things, but ways that seem more like toys or bro-speriments than anything with wide commercial value.

We think this is a misunderstanding of the deep forces at work. People are fumbling toward ways to use money to support a deep need for resiliency and hardening with regards to a society in flux. Fin-tech, broadly, crypto technologies and web3 more specifically, are just the manifestations of that instinct. Some of it will play out in higher velocity, some in less friction, some in new means of exchange or savings, and some in—surprise!—new and overdue financial frictions.

Starting with the last one first, here is one way to think about it: The rise of web3 and blockchains can be seen as a reaction to the lack of resilience in a centralized system, and doing so introduces some interesting dynamics. For one thing, the majority of web3 advocates will maintain that their goal is to remove friction from the system, but in reality, in the short-to-intermediate stages of moving to a fully decentralized network, what is actually introduced is more friction. This is easily identifiable by anyone attempting to use blockchains like ethereum, where gas fees and ease-of-use problems are clearly mechanisms of friction and slack.

None of this is to say that the eventual outcome isn’t a reduction in said friction and slack, but that way station is much further down the development road than most advocates think at this point. And yes, we can hear large segments of the crypto/web3 ecosystem laughing at the thought that they’re currently introducing more friction into the world of finance. It’s okay, we kind of treasure being laughed at for our investment stances.

Another way slack, friction, and resiliency is coming into the system is via the WFH movement. Most obviously, and as increasing numbers of studies show, WFH is an inherently less-productive mode of working. Perversely, this is probably a good thing. We have seen the societal consequences of tight coupling too often lately—from viruses to supply chains—and new frictions are welcome, even if unexpected.

But WFH is creating resilience in other ways, much less well understood. By severing the physical relationship between one’s work and one’s location, it is tacitly loosening the relationship between employer and employee. People are increasingly thinking of work as a thing they do, alongside other things they do, many of which may be other forms of paying work. In other words, WFH is driving a portfolio approach to employment, gigs of gigs, an approach that will provide them more economic resiliency, which accrues benefit to society when people are no longer stuck in monolithic, inflexible, over-optimized work relationships. One can very easily see how this decoupling of employer and employee readily leads to a decoupling of health insurance being provided primarily by a sole employer, for example.

We can see many examples of this move to portfolios that provide resilience, some of which can seem unusual, to say the least. Consider the rise of niche hobbies, like, sports cards and sports betting, and so on. These are becoming more easily accessible, fractionalized and monetized. While they may or may not be the future of new work portfolios, they do represent early, fumbling attempts to adapt, harden and make more resilient one’s economic life via diversified income streams.

From an investment perspective, this new lens of economic resilience highlights many linked opportunities that might otherwise seem disjointed. But whether it’s an investment in a web3 messaging protocol (xmtp), in a sports card startup (NextGem), or in a startup that allows renters to turn their security deposit into a line of credit (Roost), they are all investments in resilience (in the examples cited above, our recent investments in resilience).

Future Societies (in the U.S.)

Perhaps the most complex and important area where we will see immense changes ahead is in the very structure of society. Words like hardening and resilience get thrown around, but we see immense changes coming, much bigger than most people are willing to consider.

We will start with the idea that hardening against environmental change is largely a myth. For example: sure, it doesn’t hurt to cut back foliage ten yards from your house if you live in a fire-prone area of the western U.S., but wind-blown fires that regularly cross multi lane freeways won’t be stopped by less oleander or thinned pines.

Further, to the extent we induce more people to live in fire-prone areas by “hardening” them, we are almost certainly making the problem worse. Most wildfires have human causes, and bringing more humans and more powerlines into contact with more drying fuels will only lead to more fires, mitigating the risk reduction we had previously achieved.

Similarly, there is a huge body of research showing the unintended impacts of coastal hardening, usually done to protect beach-front or near-coast homes. More often than not, such structures accelerate the pace of erosion, due to the absence of beach replenishment because of armored cliffs. It creates an expensive cycle of further protection and further beach replenishment, all in the name of a doomed attempt to harden the coast against rising sea levels, thus increasing storm severity, and increased coastal dwellings.

Such dramas are playing out around the world. It could be drought, heat, coasts, or fires, but we convince ourselves that we can harden against these forces. And we can, to a point, but not always, and not at the scale required, and certainly not without unintended consequences, as discussed above. Larger populations, prevented from starving, creates more pressure during the next drought or famine. Groundwater and canal-serviced communities grow, putting more pressure on shrinking water supplies; all amidst ever-more frequent droughts and shrinking aquifers.

The bottom line, for us: you cannot fully harden your way out of a fundamental change in complex systems. These systems have a way of moving against you in unexpected ways, often fueled by the very forces you put in play to protect yourself. Add to that the fact that the move usually goes against the maximum number of people possible, and, well, cascading problems ensue.

It will be very, very hard for societies and their governments to realize this doesn’t work. It will be particularly hard, perversely, in developed economies, where governments and the wealthy can throw money at the problem, convincing themselves it’s being managed. This will be true, until it isn’t, and then it will go calamitously wrong, seemingly overnight, with many people who thought they were safe, exposed to vastly higher risks.

We think the longer future, perhaps outside of our investment horizon, will bring unexpected change. Wildfires, drought, water scarcity, and coastal flooding will put billion and then trillion-dollar pressures on governments to manage it. And it will be increasingly clear, as the costs mount, that it cannot be managed, at least not in the hardening sense that has become parlance.

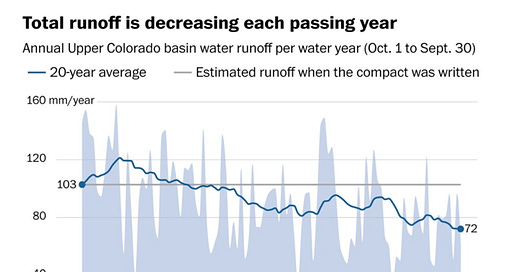

So, what will happen? Let’s go full scifi—a weirdly underused ploy in venture—and imagine life in 2050. Seas have risen more than a foot, temperatures have risen more than 1.5 C (that’s 2.7 F for those of you that aren’t Canadians), droughts are more common, and the west’s fire season is year round. Eastern states are caught in a multiyear lawsuit against western states over being downwind of wildfire-related smoke, with dramatic health consequences. Meanwhile, western states are still in a drought that is like one not seen in over 1500 years. The Colorado River is 25% smaller, as are many of the west’s largest rivers, and the snowpack has become less predictable and shorter lasting. The first tentative stabs have been made at geo-engineered cooling by high-altitude sulfur emissions, with uncertain future consequences.

It is our belief that, in this future-scape, the U.S. is set for the largest population relocation in its history. We will see climate-refugee colonies. Colonies focused on relocation to areas that can provide abundant fresh water – perhaps private equity financed. Massive new cities pop up in the Great Lakes area, as proximity to water becomes vital, and the government can no longer guarantee a secure water supply in much of the west. We could see tens of thousands of new homes in states like Michigan and Wisconsin. States where winters are now suddenly much shorter, that are beneficiaries of freshwater lake and rain water supplies.

Managed retreat will become the new hardening. After decades and billions spent trying to prevent it, the U.S. reverses, actively encouraging its citizens to relocate, given that it can no longer keep them safe from fires and drought, nor guarantee reliable water supplies. We think this is a plausible future, one that few people are thinking about.

This is all fascinating, we hope, but the right reaction is to think: what does it mean for investors? Well, we think this will play out in relevant ways much sooner than 2050. Confronted with a changing environment, people will look to hardening, but they will also look to resilience, to protecting themselves and their families from something they sense in their gut, more than they understand in their heads.

This is already happening to a limited degree. People are looking for ways to increase their personal resilience in small ways, even if they might not call it that. We see larger food stores, more savings, and, of course, more guns and ammunition sales. These can all be seen as fumbling attempts to manage lived experiences that feel more volatile than ever, and at the mercy of forces people can’t control. This feeling will grow to an emotional tsunami that washes over the population in the coming years.

—---

To return to the present, all of these themes link together for us as we think about the future. Rather than seeing it somehow dystopically, we think the prior period was the anomalous one, where people could rely on seas staying peaceful, and they are learning the consequences of being wedded to placidity. We see these opportunities through the lens of the Stockdale paradox, an approach we see as an immunization against negativity.

This is why we think all of these ideas we’ve discussed here—energy, friction, relocations, financial mobility, and health, etc.—are linked. We think they are part of a much bigger meta-theme of resilience, of society finding new ways to adapt and even thrive in a more volatile world. The result will be a stronger society, one less easily buffeted by change, because those changes are an inevitability.

—---