Integrating the Goldman AI Report Into Our Views

There is a new Goldman Sachs report out today with a headline claim that 300m+ jobs worldwide could be affected by generative AI. We think that it is worth integrating this into our recent work, to show that this claim is both bigger and smaller than it should be.

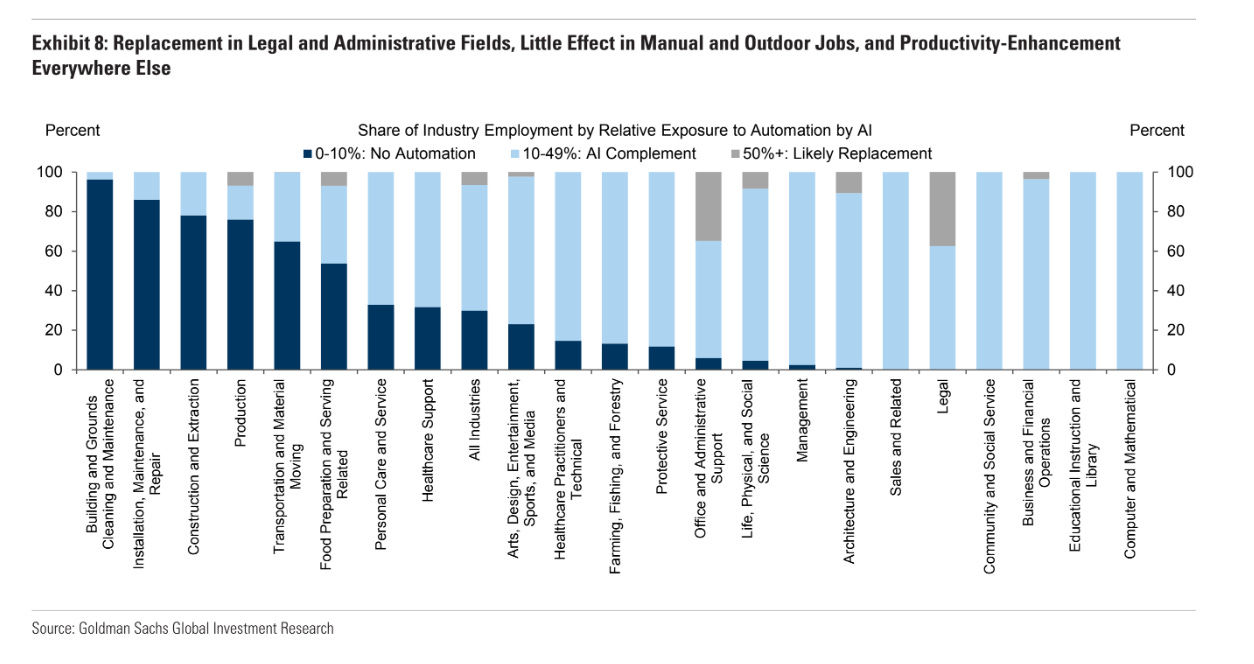

Goldman applies a fairly traditional displacement vs augmentation framework, considering which occupations that are affected are likely to be displaced (replaced) vs which ones are more likely to be augmented. It also considers which jobs are less likely to be affected at all, and those positions are mostly in more labor-intensive fields like building construction, unsurprisingly, where replacing labor with capital is still very expensive, if even possible.

Here is a key graph from the Goldman report, showing the displacing/augmenting framework across a host of fields, as well as showing occupations less likely to be affected.

Based on this, Goldman’s analysts go on to argue that there could be significant disruption to worldwide labor forces, especially in regions whose economies are more skewed to occupations toward the right side of that graph, and less so on the left. Further, it argues that there could be significant productivity improvements in the coming years, based on these changes, leading to higher economic growth than trend, even if accompanied by significant disruption.

We don’t disagree. We would, however, caution that Goldman’s approach is fairly traditional, in that it treats the prospective productivity gains across various disciplines as a function of the ease of applying these generative AI technologies, as opposed to the availability of low-hanging economic fruit. We think the gains from making it easier to produce presentations and documents and emails are much less than touted.

On other hand, we stand by our argument that the gains of generative AI in other occupations are large, and larger than Goldman anticipates in this report. Again, and more specifically, we think that the gains from producing software are very large, given that, as we’ve argued, we have underproduced for decades, and software sits in the sweet spot with respect to its combination of a clean grammar and logical structure, and given that it has been too costly to produce for most of its existence, hence why it’s been so slow to “eat the world,”as has sometimes been said is happening.

As we’ve stated previously, software’s underproduction worldwide has led to a kind of society-wide technical debt, which is largely misunderstood but is immensely important. This new Goldman report, while useful, mostly sticks to a more traditional view of the disruptions and opportunities ahead.